Kate’s novel biographies

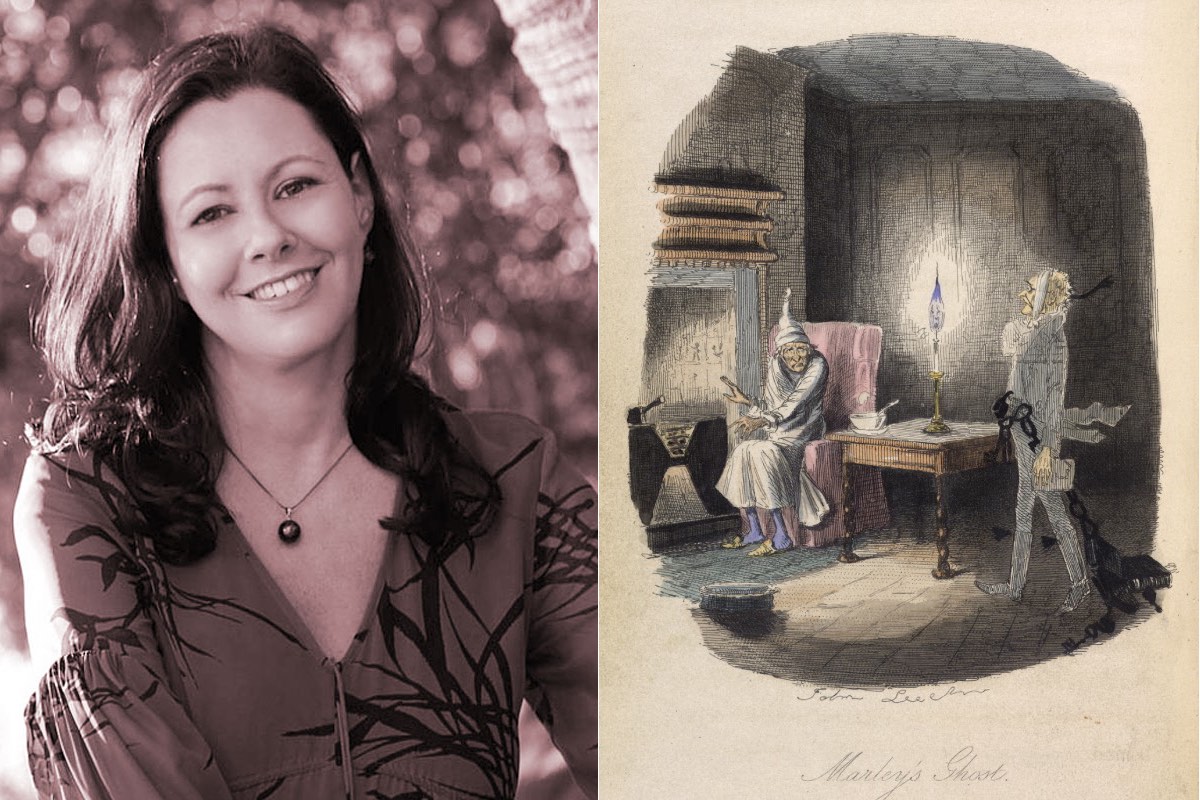

Title: A Christmas Carol

Author: Charles Dickens

A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens was published 176 years ago, on December 19th 1843, but its popularity only continues to grow with a new generation of movies including The Man Who Invented Christmas two years ago.

It’s one of my own personal favourites of his works, simply because of its vitality and Dickens’ signature mix of joyousness and poignancy. I like to re-read every year at Christmas – it only takes an hour or so, with a glass or two of mulled mead and perhaps a thick wedge of fruit cake.

Everyone knows the basic outline of the story – a miserable old miser named Scrooge refuses to celebrate Christmas, uttering “Bah! Humbug!” every time it is mentioned:

Oh! But he was a tight-fisted hand at the grindstone, Scrooge! a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner! Hard and sharp as flint, from which no steel had ever struck out generous fire; secret, and self-contained, and solitary as an oyster. The cold within him froze his old features, nipped his pointed nose, shrivelled his cheek, stiffened his gait; made his eyes red, his thin lips blue; and spoke out shrewdly in his grating voice.

Scrooge is visited by the three ghosts of Christmas Past, Christmas Present and Christmas Yet to Come, and is consequently transformed and redeemed, learning kindness, compassion and the proper Christmas spirit.

I don’t know what to do!” cried Scrooge, laughing and crying in the same breath; and making a perfect Laocoön of himself with his stockings. “I am as light as a feather, I am as happy as an angel, I am as merry as a school-boy. I am as giddy as a drunken man. A merry Christmas to every-body! A happy New Year to all the world! Hallo here! Whoop! Hallo!

Many people do not know the fascinating life story behind the writing of this great children’s classic.

Dickens had a normal happy childhood in the country, where he loved a snowy white Christmas with all the old folk traditions. When he was twelve, however, his father was thrown into debtors’ prison and Charles was sent to work in a factory. The hardship and humiliation of this experience gave him a deep understanding of social injustice, as well as a love of all the fine things in life of which he had been deprived.

He began work as a journalist in his teens, and started publishing humorous short stories when he was only 21. Only 400 copies of the first instalment of Sketches by Boz were published, but by the 15th instalment, 40,000 copies were printed.

The success of the Pickwick Papers led to a swift succession of novels: Oliver Twist (1838), Nicholas Nickleby (1839), The Old Curiosity Shop (1840), Barnaby Rudge (1841), and Martin Chuzzlewit (1843). Each book was less popular than the one which came before, and Charles Dickens was now supporting a wife and numerous children. His publishers Chapman & Hall threatened to reduce his monthly income as a result, while his wife Catherine was heavily pregnant with their fifth child.

Dickens was also filled with a strong desire to speak out about the sufferings of the poor, with a particular interest in the hard lives and cruel treatment of the young. After reading a government report lambasting the use of child labourers in mines and factories earlier that year, Dickens had vowed he would strike a ‘sledge-hammer blow . . . on behalf of the Poor Man’s Child.’

In February 1843, he visited Field Lane Ragged School and consequently wrote to The Daily News, describing the children there as ‘the most miserable and neglected outcasts in London … the capital city of the world (and) a vast hopeless nursery of ignorance, misery and vice; a breeding place for the hulks and jails.’

At first he imagined writing some kind of angry political diatribe, but it was not long before he realised that a story is the best way to change the world.

Dickens began writing A Christmas Carol in late October 1843, and wrote as if in a fever. The Cratchits were constantly ‘tugging at his coat sleeve, as if impatient for him to get back to his desk and continue the story of their lives,’ he wrote later. He imagined most of the book while walking for miles at night through London, then wrote for most of the day. His sister-in-law said he ‘wept, and laughed, and wept again, and excited himself in a most extraordinary manner.’

The book was completed in six weeks, the final pages being written in early December. A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas, was published only a few weeks later, on 19 December. The first edition sold out by Christmas Eve, and has never been out-of-print.

It has been said that Dickens singlehandedly created the iconic idea of Christmas as seen on greeting cards – a laughing family gathered by the fire, a Christmas tree glowing with lights, snow falling outside the window, presents piled high, and of course, the quintessential Christmas feast:

Such a bustle ensued that you might have thought a goose the rarest of all birds; a feathered phenomenon, to which a black swan was a matter of course — and in truth it was something very like it in that house. Mrs Cratchit made the gravy (ready beforehand in a little saucepan) hissing hot; Master Peter mashed the potatoes with incredible vigour; Miss Belinda sweetened up the apple-sauce; Martha dusted the hot plates; Bob took Tiny Tim beside him in a tiny corner at the table; the two young Cratchits set chairs for everybody, not forgetting themselves, and mounting guard upon their posts, crammed spoons into their mouths, lest they should shriek for goose before their turn came to be helped. At last the dishes were set on, and grace was said. It was succeeded by a breathless pause, as Mrs Cratchit, looking slowly all along the carving knife, prepared to plunge it in the breast; but when she did, and when the long expected gush of stuffing issued forth, one murmur of delight arose all round the board and even Tiny Tim, excited by the two young Cratchits, beat on the table with the handle of his knife, and feebly cried Hurrah!

… now, the plates being changed by Miss Belinda, Mrs Cratchit left the room alone — too nervous to bear witness — to take the pudding up and bring it in.

Suppose it should not be done enough! Suppose it should break in turning out! Suppose somebody should have got over the wall of the back-yard, and stolen it, while they were merry with the goose — and supposition at which the two young Cratchits became livid! All sorts of horrors were supposed.

Hallo! A great deal of steam! The pudding was out of the copper. A smell like a washing-day! That was the cloth. A smell like an eating-house and a pastrycook’s next door to each other, with a laundress’s next door to that! That was the pudding! In half a minute Mrs Cratchit entered — flushed by smiling proudly — with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing in half of half-a-quartern of ignited brandy, and bedight with Christmas holly stuck into the top.

It’s not quite true that Dickens invented Christmas. Other forces – including the importation of German customs by Prince Alfred, Queen Victoria’s husband and the invention of the Christmas card in 1843 – also played a part.

For many people, A Christmas Carol is sickly-sweet and sentimental, particularly the scene showing a future Christmas where the crippled boy Tiny Tim has died. Certainly Dickens was not averse to plucking at the heartstrings, and often wrote scenes where angelically good children die (Oscar Wilde wrote of another one of Dickens’ dying children: ‘one must have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell without laughing.’)

Dickens’s hand-written manuscript of the story does not include the sentence in the penultimate paragraph in the published book … and to Tiny Tim, who did NOT die, (Scrooge) was a second father.

This saving grace was added later, during the printing process.

Some see this as a corrected oversight, others as a later moment of revelation for Dickens as he realised the importance of showing that Scrooge’s redemption has changed his world for the better.

Let’s end on one of my favourite liens from the book:

I have always thought of Christmastime, when it has come round…as a good time; a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time; the only time I know of, in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys.